Autonomy is easy to admire when it works.

Give an agent a goal, access to a few tools, and the ability to reason, and it starts to feel almost magical. It retries intelligently when something fails. It adjusts its plan. It keeps moving forward without needing to be nudged. In demos, this looks like real progress.

Autonomy itself isn’t the problem.

There are many areas where agents should be free to operate. Summarizing reports. Synthesizing information. Exploring hypotheses. Drafting explanations. When agents get these wrong, the cost is usually low and easy to recover from.

Problems begin when the same level of freedom leaks into higher-risk areas. Once an agent can escalate a case, mutate state, or influence irreversible outcomes, the cost of “just trying again” becomes very real.

The mistake teams often make is treating autonomy as binary, either fully allowed or fully restricted. In practice, autonomy needs to be selective.

Why Static Governance Falls Apart at Runtime

Most governance mechanisms operate before execution begins. Policies are written. Prompts are constrained. Tools are allow-listed. Offline evaluations are run. On paper, this all looks sufficient.

In production, behavior is shaped by context. Latency spikes. Partial failures occur. Data arrives late. A retry that made sense once becomes harmful when repeated across hundreds of parallel workflows. Static governance can explain intent. It cannot enforce behavior once conditions change.

This is usually when teams realize that observability alone doesn’t help much. Knowing that an agent entered a loop does not undo the impact. By the time dashboards light up, the system has already drifted out of bounds.

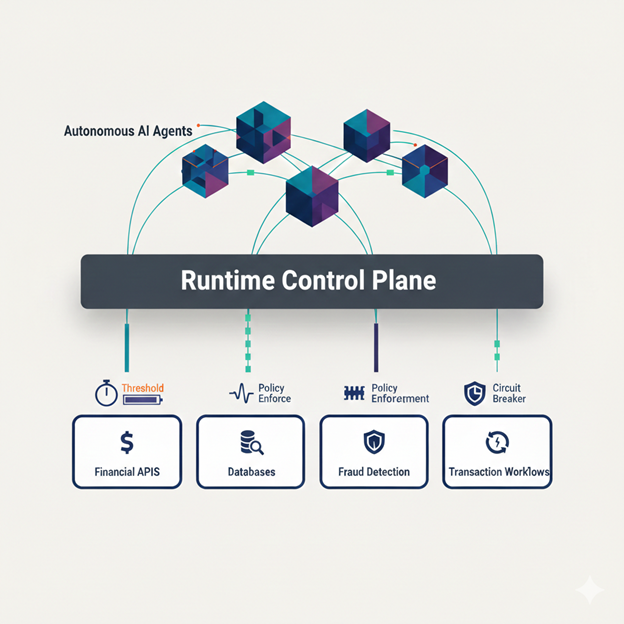

Runtime Governance as Boundary Enforcement

Runtime governance exists to answer a simple but critical question: what is this agent allowed to do right now, in this context?

It doesn’t attempt to control how an agent reasons. Instead, it sets boundaries around what the system is permitted to execute while that reasoning is happening. How long an agent can run. How many retries are acceptable. When confidence is sufficient. When escalation must stop. When execution needs to be handed off to a human.

These ideas aren’t new. Financial systems have relied on similar constraints for decades. What’s new is the need to apply them while decisions are unfolding, not after the fact. That is why runtime governance feels less like policy enforcement and more like boundary design.

Over-Governing Is a Failure Mode Too

There is an equal and opposite mistake teams make.

Faced with risk, some organizations clamp down everywhere. Every action requires approval. Every decision is gated. Every workflow slows to a crawl. Autonomy is reduced, but so is the value agents were meant to provide.

Latency increases. Humans become bottlenecks. Systems become brittle in ways that are harder to predict. Good runtime governance doesn’t minimize autonomy. It places it deliberately. High autonomy where failure is cheap. Tight boundaries where failure is expensive.

That balance is not a compliance checkbox. It is an engineering decision.

Trust Comes From Predictable Failure, Not Perfect Behavior

No runtime governance system makes agents perfectly safe, and that is not the goal. Production systems do not need perfection. They need predictable failure. When something goes wrong, the system should stop cleanly, surface the issue, and leave behind enough context to understand what happened.

Poorly governed systems fail silently and expensively. Well-governed systems fail early and visibly. In fintech environments, that difference often determines whether teams are willing to trust autonomous systems at all.

Closing Thought

The future of agentic AI in fintech will not be defined by how autonomous these systems become. It will be defined by how precisely that autonomy is bounded.

That line between freedom and control is not theoretical. It is where real systems either hold together — or quietly fall apart.